Janus — Roman God of Transitions, Beginnings and Endings

- Main

- >

- Roman Mythology

- >

- Roman Pantheon of Gods

- >

- Janus

He saw both past and future at once. And at the end, you’ll learn why his temple was never closed.

Janus is one of the oldest and most enigmatic deities in the Roman pantheon—he’s not borrowed from the Greeks; he’s purely Roman. Janus is the god of transitions, beginnings and endings, gates and doors. He opens the year, the month, the day, and every new venture. According to tradition, he has no defined parents and is considered eternal.

Janus

JanusOrigin and Unique Nature of Janus

Janus is so ancient that even in Augustus’s time his ancestry was debated. Some called him Latin or Sabine. His name comes from the Latin ianua, meaning "door," hinting at his role: overseeing entrances and exits, beginnings and conclusions.

According to sources like Livy, Janus had no Olympian lineage—he wasn’t a son or husband of any god; rather he embodied the very concept of transition itself. He is portrayed with two faces—one looks to the past, the other to the future—symbolizing opposites like day and night, war and peace, entry and exit.

Origin and Unique Nature of Janus

Origin and Unique Nature of JanusJanus as the First King of Latium

Early Roman writers such as Macrobius and Virgil claimed Janus was the first king of Latium, the land that would become Rome. Said to have come from distant eastern lands—or perhaps existing even before the Olympian gods—he ruled Latium in peace and harmony.

Legend has it that he welcomed Saturn when he fled Olympus, cast out by Jupiter. Janus sheltered and then shared power with him, ushering in a "Golden Age" of prosperity, peace, and plenty. This places Janus not only as an abstract god but also as a legendary ruler.

One legacy remains in our calendar: January (Ianuarius) is named for Janus, marking the beginning of the year.

Janus as the First King of Latium

Janus as the First King of LatiumThe Temple of Janus in Rome—The Gates of War and Peace

One of the most famous aspects of Janus’s myth is his temple in central Rome, with bronze doors that were opened in war and closed in peace. Livy reports that, during the Republic, the doors were rarely closed—only after great victories or times of peace.

King Numa Pompilius, Rome’s second king, was said to have honored Janus so much that the doors were closed during his peaceful reign. In Roman tradition, priests invoked Janus before every battle, seeking his blessing to “open the way.”

The temple was more than a shrine—it was a political symbol: open doors meant Rome was at war; closed doors meant peace had come.

The Temple of Janus

The Temple of JanusJanus as God of Rituals and Beginnings

All Roman religious rites began with Janus. No prayer or sacrifice started without invoking him first, even when honoring other gods—because Janus “opens the way.”

His epithets Patulcius and Clusius—“the opener” and “the closer”—reflect his dominion over beginnings and endings. He was associated with sunlight and the sun’s journey—morning as the “entrance into the day,” and evening as the “exit.”

Romans made offerings to Janus on the first of January and at the start of any endeavour—building, marriage, campaign—standing at the threshold between chaos and order. His two-faced image symbolizes the cycle of time, where every end becomes a new beginning.

Janus as God of Rituals and Beginnings

Janus as God of Rituals and BeginningsJanus in Roman Consciousness

Plutarch recounts a story in which Janus saved Rome from the Sabine invasion by delivering boiling water from beneath the temple, halting the attack. This established his role as protector of Rome and guardian of its gates.

Unlike other gods, Janus had no elaborate mythology or dramatic deeds. He was honored for his presence in the world’s order—in the moment that links “before” and “after.” Philosophical in nature, Janus embodied the awareness of time itself.

Janus in Roman Consciousness

Janus in Roman ConsciousnessGod of Transitions, Beginnings, and Endings

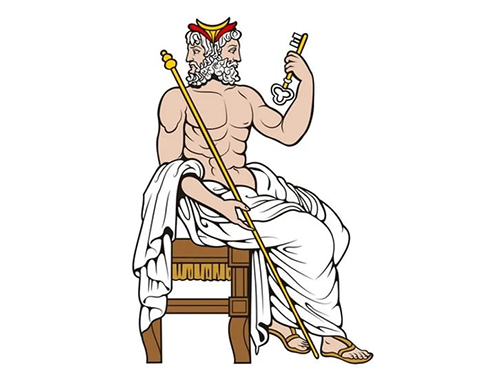

Janus is not a “god of war” or “god of fertility”—he is the god of transition. In a culture where symbols and order were paramount, he unlocked all others. His two-faced nature isn’t a flaw but his power: seeing both the past and the future.

His attributes are the key and the staff—the key to open doors, the staff to lead onward. Though the cult of Janus faded with the fall of Rome, his image lives on. The two-faced god remains associated with the transition between years, life phases, and moral choices.